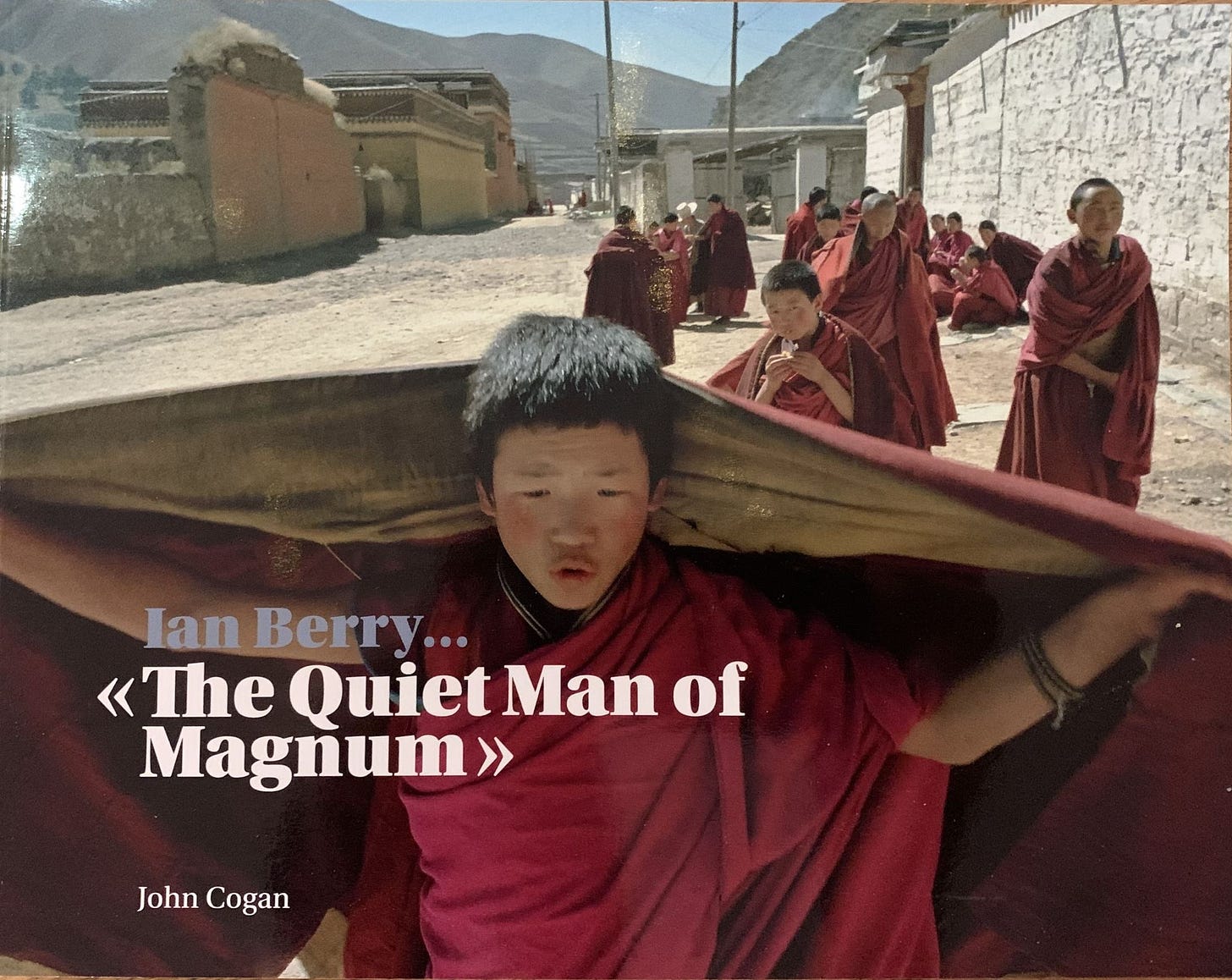

Book: The Quiet Man of Magnum

For decades top photographer Ian Berry has let his pictures do the talking. Now he has allowed a North East writer and photographer to tell his story. David Whetstone met them in Newcastle

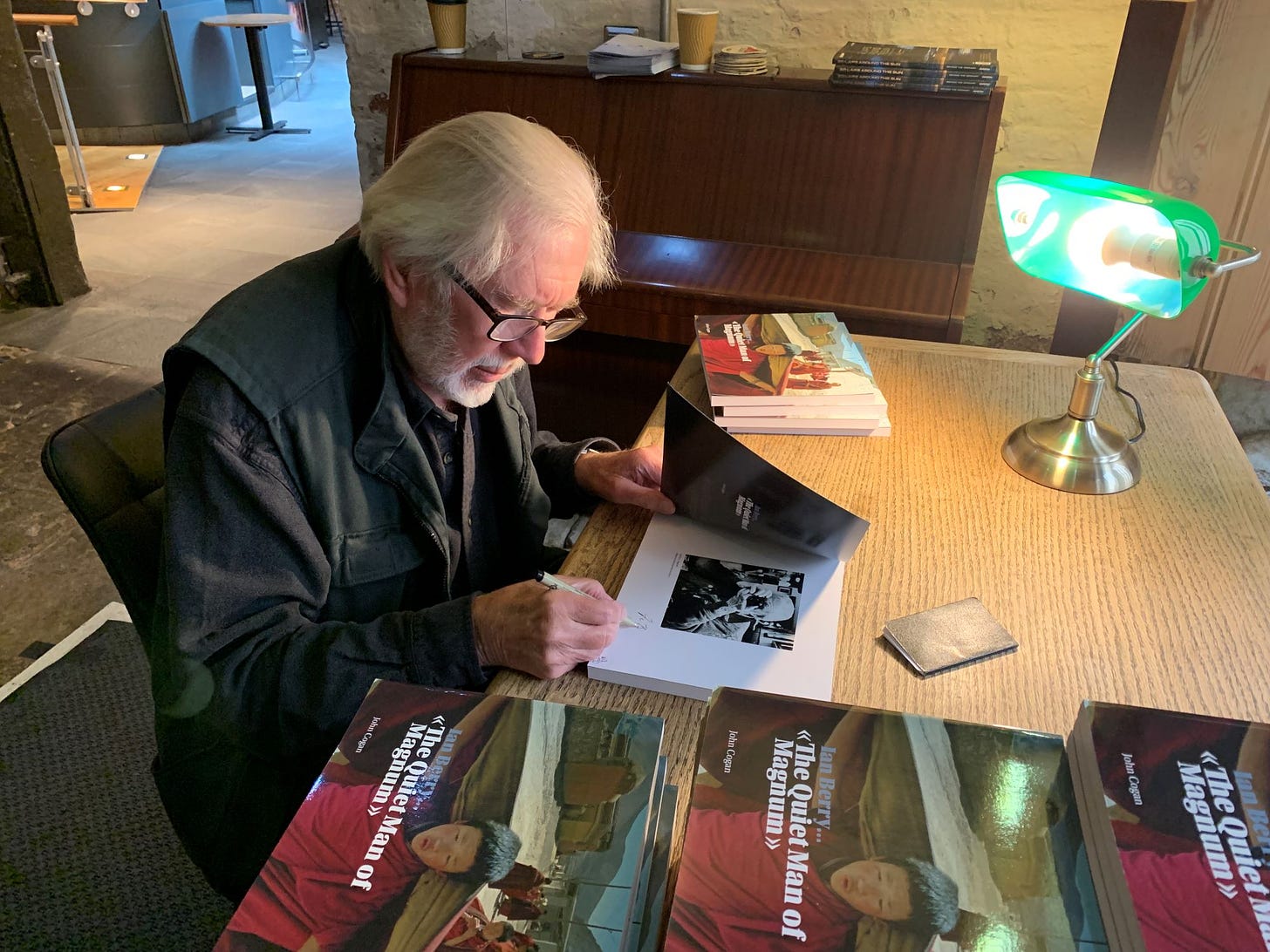

In a lamplit corner of Live Theatre’s shadowy Undercroft, Ian Berry is signing his way through the small mountain of books shortly to go on sale bearing his signature.

He is, according to the book’s title, The Quiet Man of Magnum. And that’s not the ice-cream or the handgun but the famous photo agency, established in 1947 and owned by its distinguished members.

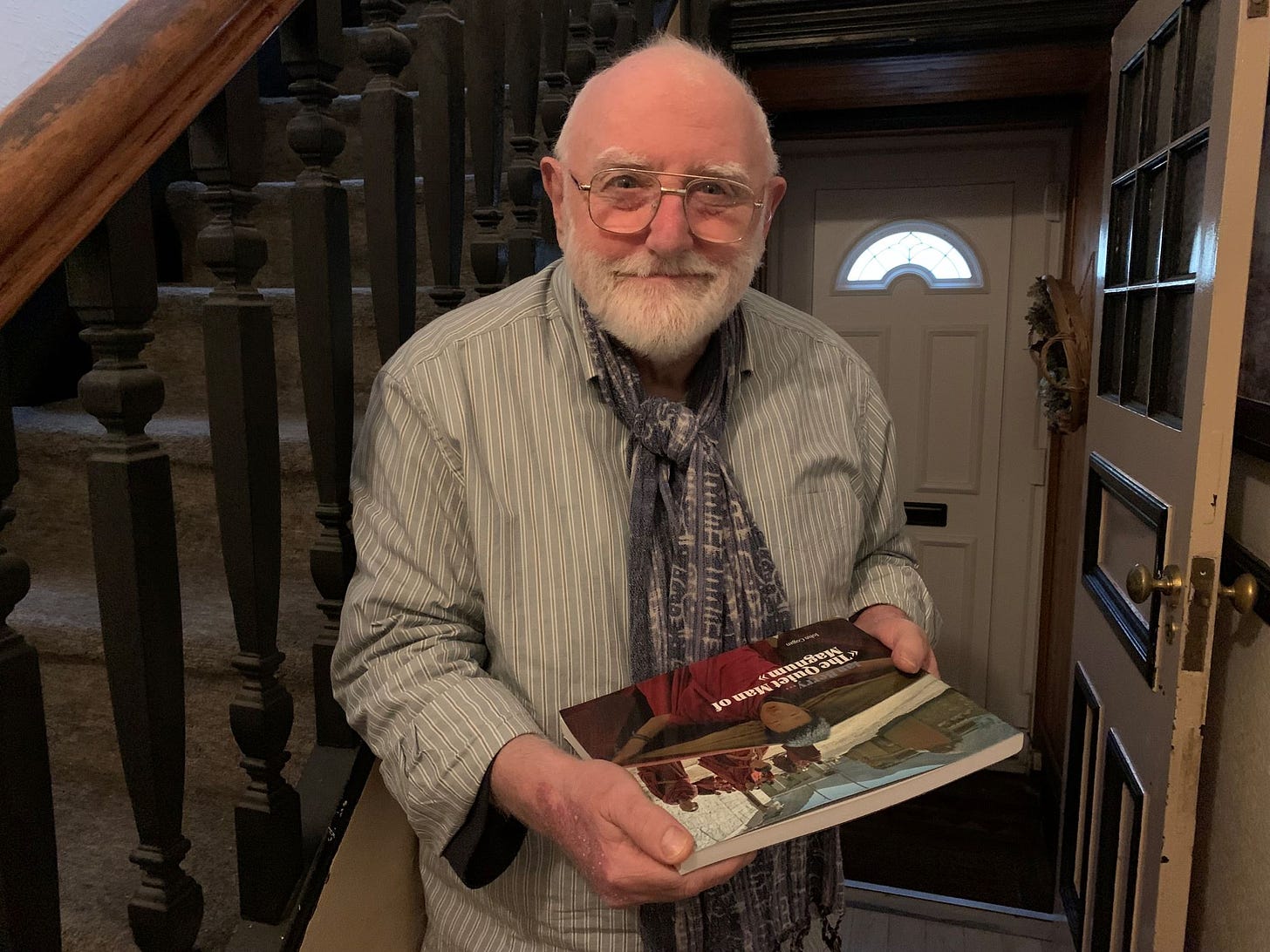

Ian, who joined in 1962, is now the longest-serving full member of Magnum Photos and this is his life story, a 10-year labour of love by John Cogan, retired headteacher and keen amateur photographer from Hetton-le-Hole.

It’s an extraordinary story, chronicling the sometimes hair-raising adventures of a man who has borne witness through a lens to events that made history.

When working for Drum magazine in Johannesburg, he was the only photographer in the crowd at Sharpeville on March 21, 1960, when police fired on unarmed black demonstrators, killing and wounding many.

His photos of the massacre sparked outrage around the world and at a subsequent inquiry undermined the police defence of their actions, showing the crowd hadn’t been hostile and that many more bullets were fired than was claimed.

Ian, after this journalistic coup, went on to record the violent upheaval accompanying Congo’s independence in 1960, at one point being put against a wall before a jittery firing squad.

Then in 1968 he was one of very few photographers to witness the brutal suppression of Czechoslovakia’s peaceful uprising, the so-called ‘Prague Spring’, arriving as Russian tanks rolled in.

For more than 60 years, as the book relates, he has been a globetrotting witness to the best and worst of humanity.

He has been close to the action in Vietnam, the Middle East and Northern Ireland during the ‘Troubles’. In 1966 he captured the aftermath of the tragedy in Aberfan where a colliery spoil heap engulfed a primary school.

In Iran, photographing women in billowing black clothes boarding a bus via the rear door (men used the front), he ran into trouble when a woman glanced back, as he’d hoped would happen.

A watching mullah took umbrage at his photographing a woman’s face and he was hauled before local police.

Ian, John stresses, resists labels that might pigeonhole him. While he has photographed in many a war zone, he doesn't call himself a war photographer. It’s the same with any other genre.

“One thing I’ll say about Ian is he’s fascinated by people,” says John. “Other photographers can happily take photos of Roman remains in the desert but Ian’s invariably have a person in them somewhere.”

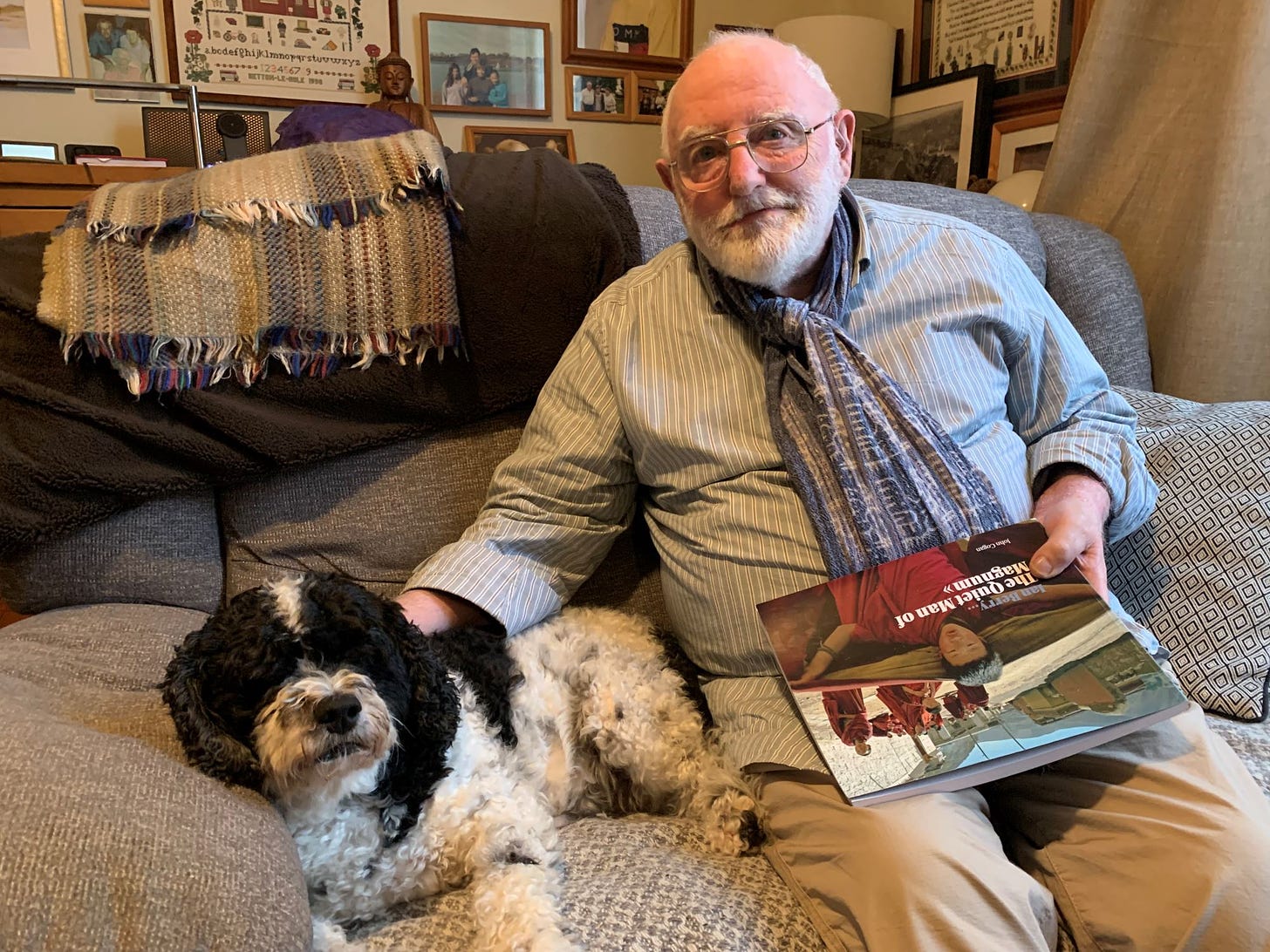

Ian, born in Preston and now living with wife Kathie in Salisbury, says this is true.

“I’ve always been interested in people. I started out wanting to be a journalist but realised very quickly that I couldn’t write my own name.

“I was an amateur photographer at the same time and that eventually enabled me to spend my life running round the world, meeting people and getting to know the social situation in different countries and what was going on.”

Ian moved to South Africa when in his teens and after learning his trade from a professional photographer began working for newspapers.

When he learned that Tom Hopkinson, former editor of the famous Picture Post, was coming to edit Drum, he “pestered” him for a job and got one.

Drum targeted readers in the black townships and employed black and white journalists (a colleague, Peter Magubane, would one day become Nelson Mandela’s personal photographer). It was not liked by the apartheid-enforcing government.

After eight years in South Africa, Ian moved to Paris and then back to Britain where he became the first photographer contracted to the fledgling Observer magazine in the days, he smiles, when “money was no object”.

It’s rather extraordinary to find him quietly signing books in Newcastle, home of Allies Group, which agreed to publish John’s manuscript when he brought it to them.

“Ian Berry is a very modest gentleman,” says John in the book, recalling their first meeting when he was writing about documentary photographers for the Royal Photographic Society.

John says while he would often get excited about one of Ian’s stories, Ian would respond with: “Do you really think anyone would be interested in that? The pictures were not that good.”

Ian has had plenty of other books published, two about South Africa and his most recent, published last year, about our relationship with water.

They are photography books wedded to the idea that a picture is worth a thousand words. Probably Ian would never have published a book like this, telling his own life story in thousands of words.

“John was the reason for it because he approached me and said how about doing it?” he says. “It was his idea. He wrote it and it’s his book.”

John alludes to the ‘Boy’s Own’ quality of parts of the narrative. He’s not wrong.

Of the time in the Congo when he and two other photographers were put before a firing squad in the breakaway state of Katanga, he tells me laconically: “These things happen but I think you get used to it and take it in your stride somewhat.”

The three were saved by a Rhodesian mercenary who told the jittery Katangese troops that he would take their captives to the president. He did so and President Moïse Tshombe offered them tea and biscuits.

The camera lens, agrees Ian, has a distancing effect. “It separates you from what’s going on.”

At Sharpeville, though, he found himself in the thick of the action when the police started shooting and people ran.

“I’ve been shot at a lot since then and sometimes it was a lot more scary because this happened so quickly,” he recalls.

“There was no warning. In fact I was about to leave because I thought nothing was going to happen and when they started shooting I thought either they were shooting blanks or they were shooting over people’s heads to get rid of the crowd.

“Anyway this woman was shot next to me and then I realised they weren’t blanks.”

Entering Czechoslovakia in 1968 involved the “rat-like cunning” and “plausible manner” once cited by foreign correspondent Nicholas Tomalin as necessary attributes for a successful journalist (Tomalin, with whom Ian worked in Vietnam, was killed in 1973 covering a war in the Middle East).

Read more: Exhibition for the eyes and ears at Woodhorn

Told to make haste by his bureau chief early one morning, Ian found his visa had expired so by the time he got to Heathrow all seats on the “logical flight” to Vienna were taken.

Instead he flew to Munich and while on the plane read in a newspaper of an architecture conference happening in Prague.

“I drove up to the border post and there were a load of journalists there. I chatted to them and they said they’d all been turned back by the Czechs. But I thought having come this far I had to give it a go.

“A Russian officer had just taken control of the border post and I think he wanted to show the Czechs that he was in charge.

“He said, ‘What do you want?’ He spoke English. I said I was going to this architecture conference. I could see the Czechs sniggering in the background because I had my camera bag on the back seat of the car.

“He waved me through so I was the only guy to get in on the same day as the Russians and I had it to myself apart from a German photographer from Stern and a Czech photographer who subsequently became quite famous called Josef Koudelka.”

Ian’s frenetic few days in Prague photographing the tanks and the outraged Czechs make for a gripping read. His dramatic photos, of course, were published widely.

John’s book also records some of the many gentler assignments that have burnished Ian’s reputation.

They gave rise to his portraits of the famous (playwright Alan Bennett, painter Francis Bacon and author Lawrence Durrell feature) and the photos – affectionate, often humorous but alive to wealth and class divides - that ended up in The English, Ian’s book of 1978.

Ian came to the North East after receiving the first grant ever awarded to a photographer by the Arts Council.

“Being a northerner it was a golden opportunity to travel around, especially in the North.

"As a photographer you’re always trying to relate people to their background. There’s a lot of really interesting architecture in this part of the world but also great contrasts in people’s social conditions.”

He was pleased with a photo he took of miners juxtaposed with Durham Cathedral and another of washing hanging between back-to-back houses in Ashington.

“When you’re walking around you’re looking for interesting people and backgrounds that might work. It’s always a case of combining the people, the background and what’s going on.

“Then you make a shape of it. One’s always looking for a shape as a photographer.

“You can do it in your own back garden but it’s much easier when you’re in unfamiliar surroundings because your eye is fresh. Salisbury is a great city but there are things I don’t see because it’s so familiar.”

Even while signing books at Live Theatre, Ian has cameras and.

“I carrem even when I’m going shopping which is stupid, I suppose. I was kind of lucky when I joined Magnum because Henri Cartier-Bresson, who was the doyen of photographers or photojournalists, was there.

“I learned an awful lot from him and he walked around with a camera all the time.”

Now aged 90, Ian is still taking photographs and planning assignments that begin at Heathrow. “It’s his job,” smiles Kathie whose own job has always been to taxi him to the airport.

Given the choice, he says, he’d be in Gaza now. But he’s mulling over a photography expedition to another hard-to-enter country which he thinks might be possible while posing as a tourist.

No placid retirement, then, for this quiet man.

Ian Berry… The Quiet Man of Magnum by John Cogan, illustrated by Ian’s photographs, is published by Allies Group at £60. Signed copies are available.

See more of Ian’s photos on the Magnum website.