Interview: Jane Lee McCracken

Artist Jane Lee McCracken, known for her stunning Biro pictures, tells David Whetstone how she has combined her twin passions – for art and wildlife – as a force for good

A kind little girl, about eight years old, once cried in her bedroom in Edinburgh, moved to tears on reading about the extinction of the Caspian tiger.

“I couldn’t understand how that could happen,” recalls artist Jane Lee McCracken. “How could this amazing species no longer exist? And why did adults let that happen?”

Adults, of course, had been wholly responsible for it happening, persecuting it for centuries and then not caring enough when it was on the brink.

Growing up in an animal-loving family, Jane spent her pocket money on wildlife magazines and the fate of the Caspian tiger cut to the quick.

“At that moment I made myself a promise that when I was older I would try to do what I could to help wildlife.”

She didn’t wait long, firing off an indignant letter to Esso about their advertising campaign which urged motorists to “put a tiger in your tank”.

Jane hoped they were donating some money to tiger conservation.

Read more: Culture Digest 02.11.24 - our weekly North East culture round-up

She doesn’t recall getting a reply. But now, in adulthood, Jane is doing extraordinary work, using art to encourage children around the world to understand and care about wildlife.

"Education," she says, "is fundamental to reversing the bio-diversity crisis."

We're talking in a Ponteland pub not far from her home (she’d have invited me there, she says, but her “adorable” Romanian rescue dog is no fan of strangers).

Jane's latest exhibition, running at the Queen’s Hall Arts Centre in Hexham until November 23, is about to open as we speak.

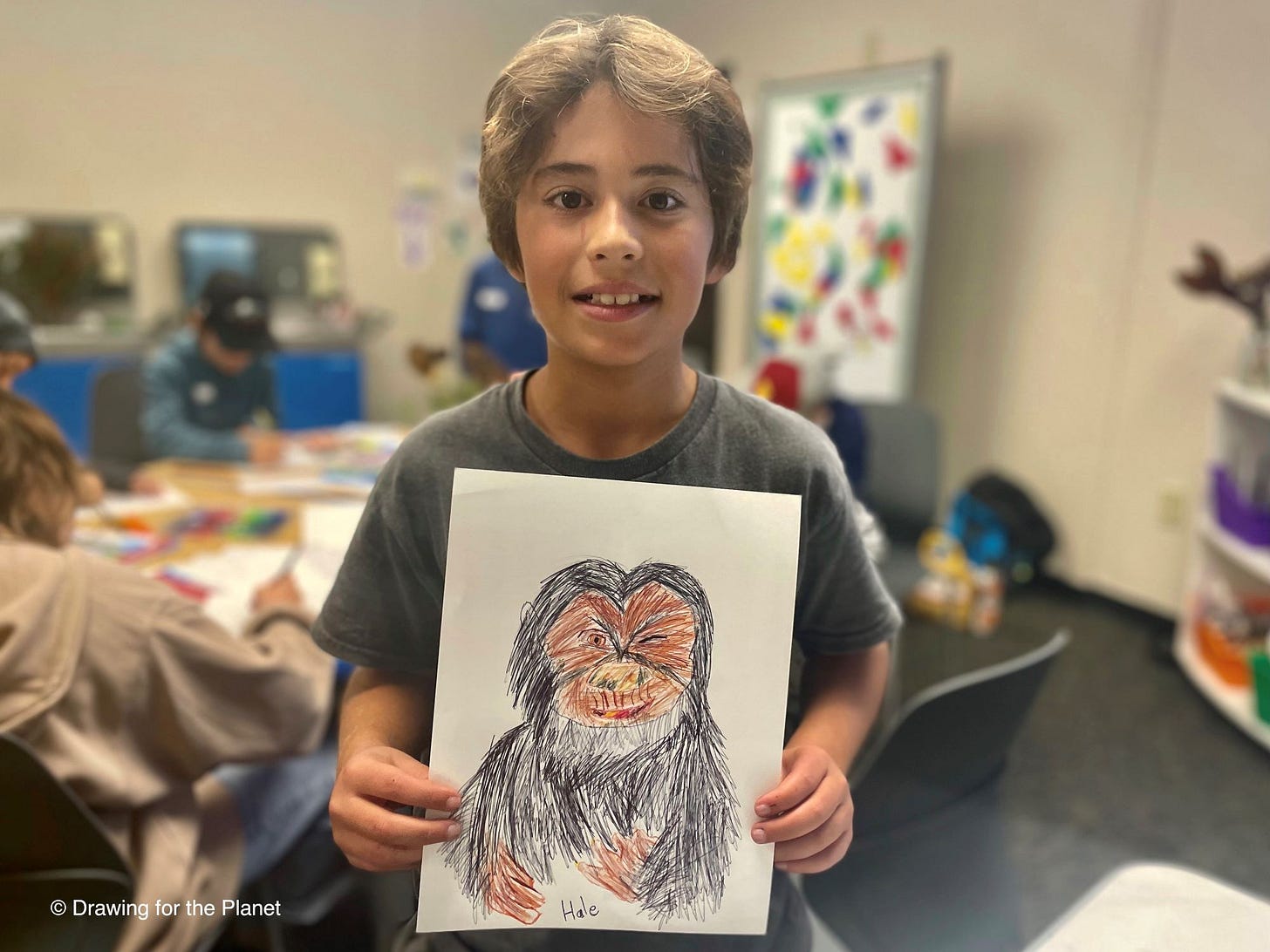

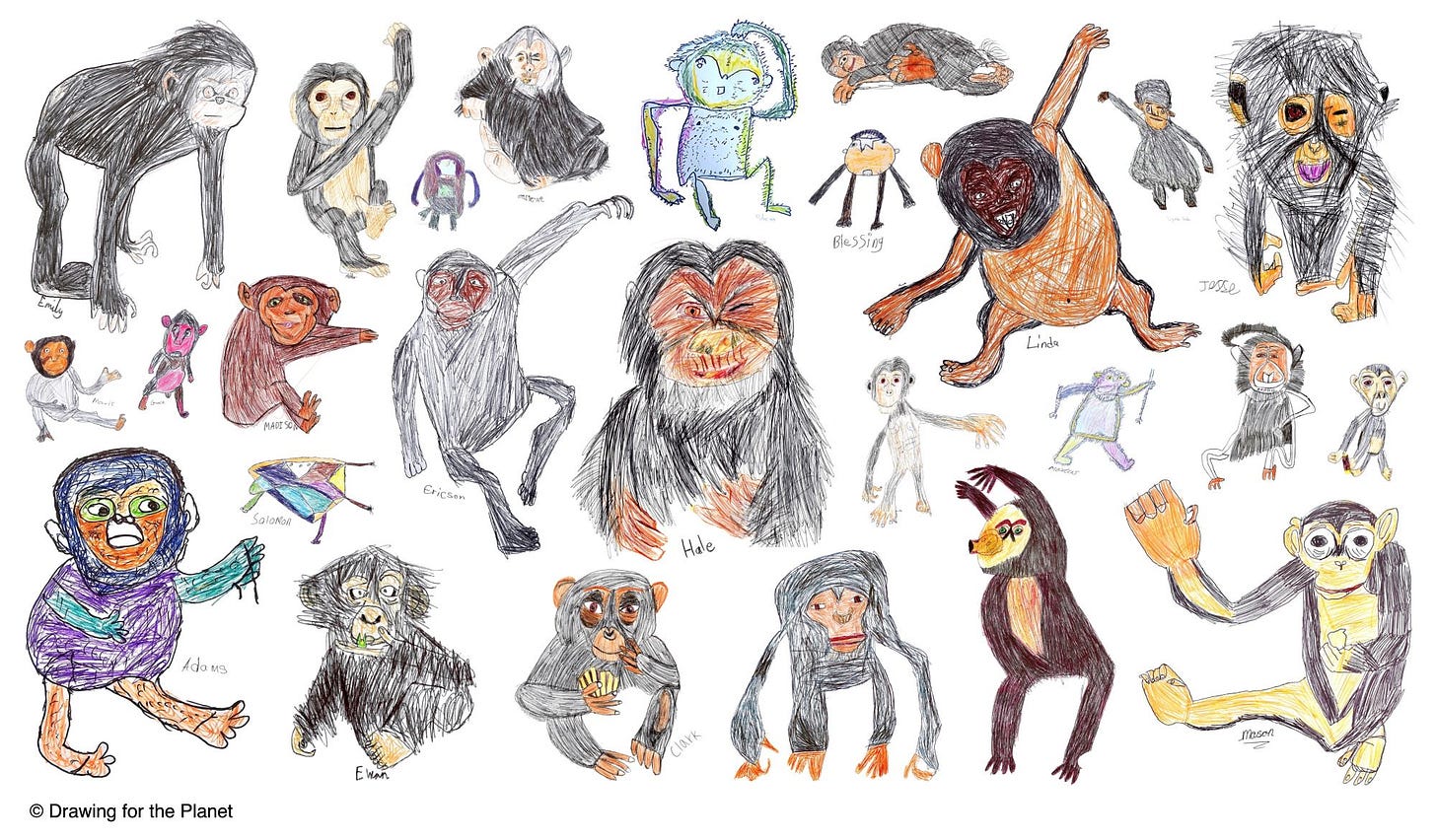

It's called Chimpanzee Community and it features drawings of chimps done by hundreds of children in Northumberland, the United States and Liberia, the latter displayed on screen since Jane and husband Rob are just back from the West African country and she didn’t have time to process them.

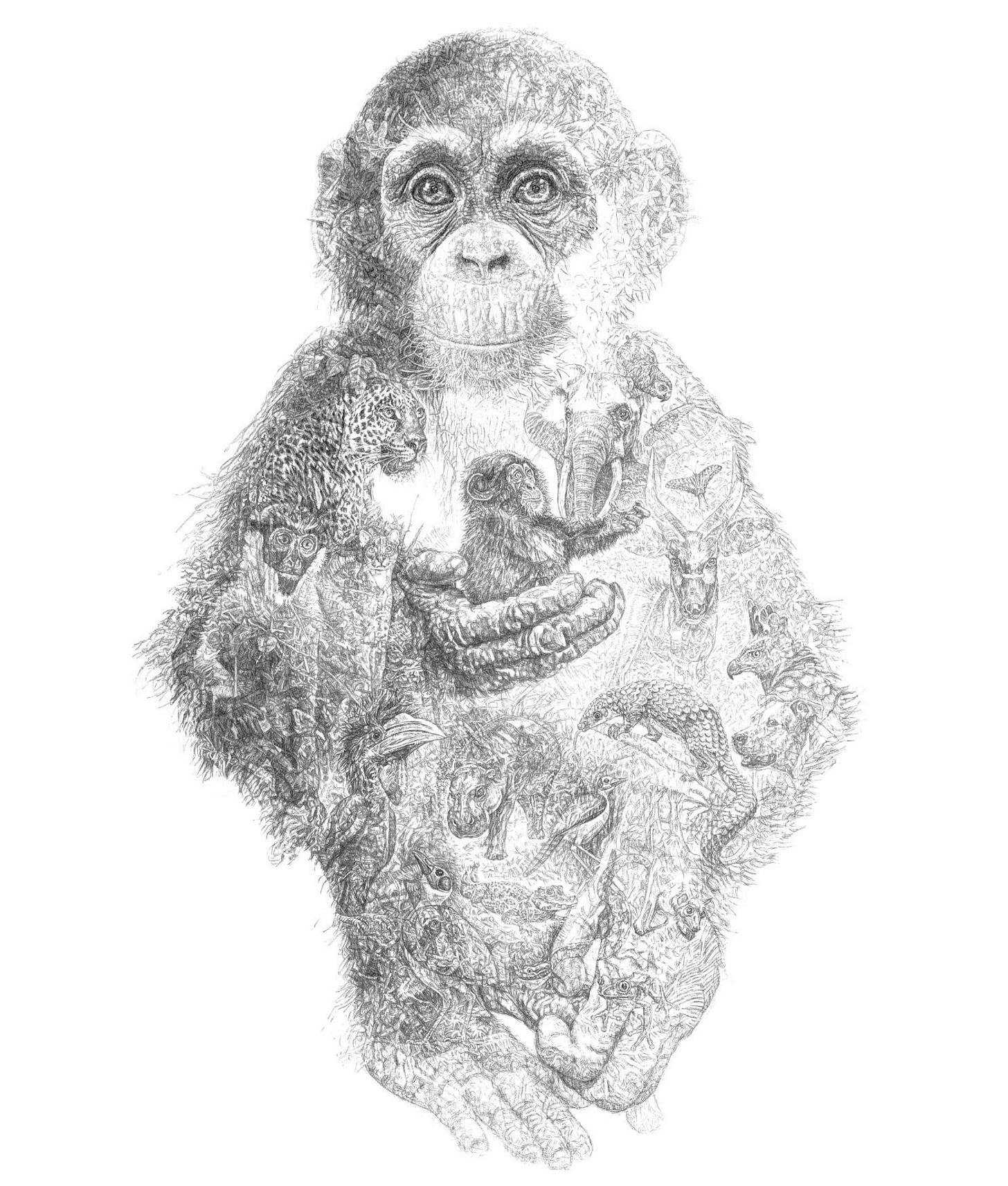

The centrepiece is Jane’s latest picture, a characteristically intricate and detailed portrait of a chimpanzee called Gardener of the Forest, the title reflecting the nickname given to these endangered creatures by people who understand their importance to the environments they inhabit.

Jane’s story is an inspiring one since she is doing precisely what she set out to do, albeit via a somewhat circuitous route.

And her art is notable because her favoured medium is the ballpoint pen which would have many other artists recoiling in horror.

As she says: “It’s incredibly unforgiving and very challenging. You can’t erase it so I’ve occasionally been three weeks into a drawing and gone, ‘Oh no, this just isn’t working’ and started again.”

She remembers her grandmother, highly creative but denied an art school education, doing deft little Biro sketches in the margins of her newspaper.

“She’d generally draw beautiful women wearing fashionable clothes. I wish I’d kept some of them but I was very young. I think that was probably the catalyst.”

Jane went to Hull and got a degree in graphic design. She moved to London and worked for a few years as a freelance illustrator but found it frustratingly limiting.

Instead she set about developing a fine art practice and took other jobs to fund it. She worked for a while as a park keeper for Camden Council and then as a guard and emergency driver on the London Underground.

It was when illness forced her off the trains and into the office that she was reunited with Biros and would use them to make little drawings on Post-it notes during lunch breaks.

In 2003, her parents having moved from Scotland to Northumberland, she moved to the county and set up as a full-time artist, producing the beautiful ballpoint pictures for which she has become known.

Jane says it was an exhibition at the Customs House in South Shields, where she was living at the time, which set her on her current course.

“I was given the opportunity to run some workshops.

“I’m quite a shy person but somehow I did it and I found I enjoyed teaching people about how I did my drawings and then getting them interested in the subject matter.

“I started thinking about how we need to educate people about how special and important wildlife is. We need wildlife but it doesn’t need us.”

Art, she understood intuitively, was the perfect vehicle.

“Art is so powerful. Children love drawing and they generally love animals so I thought this would be a good way to get into schools and use art and education workshops as a tool.”

She contacted the Born Free Foundation, set up 40 years ago to stop the exploitation and suffering of wild animals, and explained her idea for workshops called Drawing for Endangered Species, offering a percentage of her fee in return for their support.

That relationship has lasted a decade.

Out of the school workshops, and encouraged by teachers like Christine Egan-Fowler at Newcastle Royal Grammar School and Linda Peacock at Jarrow Cross C of E Primary School, came an exhibition of children’s artwork at Thought Foundation in Birtley (a venue sadly now closed).

Jane worked with seven schools, assigning each a continent to focus on. She gave a talk at each and then the children did ballpoint drawings of the various creatures under threat.

To run alongside it, Jane organised an endangered species conference that was addressed by Will Travers, co-founder of Born Free, and tiger expert Dr Melvin Gamal, “beamed in” from Malaysia.

Buoyed by the success of it all, Jane aspired to go global.

This she has done, aided by overseas friends and acquaintances including her cousin, Dr Kirsten Rogers, who lives in California and immerses herself in humanitarian missions.

Kirsten’s contacts brought Californian schools on board, along with some in Guyana in South America. With the help of Born Free and other sympathetic organisations, schools in Kenya and Malaysia were also signed up, with great efforts made to reach children in far-flung communities.

Jane had paper and coloured ballpoint pens shipped out and taught others how to deliver her workshops when she couldn’t be present.

Invariably, she says, the youngsters embraced the tasks they were set.

In the Guyana rainforest were children who had never drawn before and had no idea that the native jaguars were threatened with extinction. All the drawings, says Jane, were “beautifully expressive”.

You will know that if you saw the resulting Where Did All The Animals Go? exhibition at Great North Museum: Hancock which featured 700 drawings, all touching and often delightfully quirky.

It took place in 2021 with the world still reeling from the pandemic. It had been Jane’s lockdown project and she was sad that the children in the other participating countries couldn’t see all the pictures.

That was the motivation for founding her charity, Drawing For The Planet, which raises money so exhibitions can be mounted overseas or prints produced to hang in remote rural schools with no internet.

Jane, who is chief executive, calls it on the website “a global art, environmental education and conservation charity with drawing, one of the oldest forms of communication, at its core”.

Its projects have now reached communities in 16 countries across five continents with more than 5,400 children taking part and raising awareness of 1,660 species through their drawings.

The latest exhibition focusing on chimps was inspired by the work of Jenny and Jimmy Desmond, an American couple who founded Liberia Chimpanzee Rescue & Protection.

Jane, who often has wildlife documentaries on the TV as she draws, got in touch after seeing them and their work on a programme called Baby Chimp Rescue.

That’s exactly what they do, take in orphan chimps whose mothers have been shot, usually for ‘bush meat’ or to serve the pet trade. “I think they’re the most inspirational people I know,” says Jane.

Chimps’ DNA, she points out, almost exactly matches our own and in captivity they have a life expectancy of 60 years.

At their sanctuary in Liberia, a poor country which is home to the world’s second largest population of the critically endangered West African chimpanzee, the Desmonds are now caring for over 100 orphans.

Recently they put out an emergency appeal for extra help which shows the scale of the problem.

I ask Jane if the Liberians they met had seemed resentful of being told about the local wildlife by foreigners.

"I worried about that but no," she says.

"The kids were so thrilled to learn. Many had never drawn before and certainly not in Biro. Jenny and Jimmy, who've been there 10 years, are accepted and they’re tireless. Everyone was lovely."

Some of Jenny's photos feature in the Hexham exhibition along with Jane's film of the couple's work with chimps.

In the face of what can seem intractable problems, you wonder how those involved in wildlife conservation don't become deeply depressed.

"I’m a great believer in hope," says Jane.

"I hate unfairness and injustice but there's a lot of amazing stuff going on in the world as well.

"Showing beauty and the positive things gives a message of hope that is very important."

Just back from Liberia, Jane is likely to be in California when you read this, setting up more workshops.

Next September she's planning to go to India to run workshops for a new project called The Tigers' Forest which involves Indian children and others from the UK, the USA and Singapore.

A trip to New York, where one of her projects recently featured on the Nasdaq Tower advertising screen in Times Square, is also in the offing.

It's hard work, agrees Jane.

But she wouldn’t have it any other way. That promise she made to herself as a sobbing child keeps her going, striving to make a difference in the best way she can.