North East role in world first Gladiator battle find

Evidence is uncovered of North site’s Roman spectacle which matched man and beast. Tony Henderson reports

The first physical evidence of human vs animal gladiatorial combat in the Roman period has been revealed by a study involving North East archaeologists.

The research at a North site has uncovered compelling skeletal evidence of a human victim attacked by a large carnivorous animal, likely within the context of Roman-era spectacle combat.

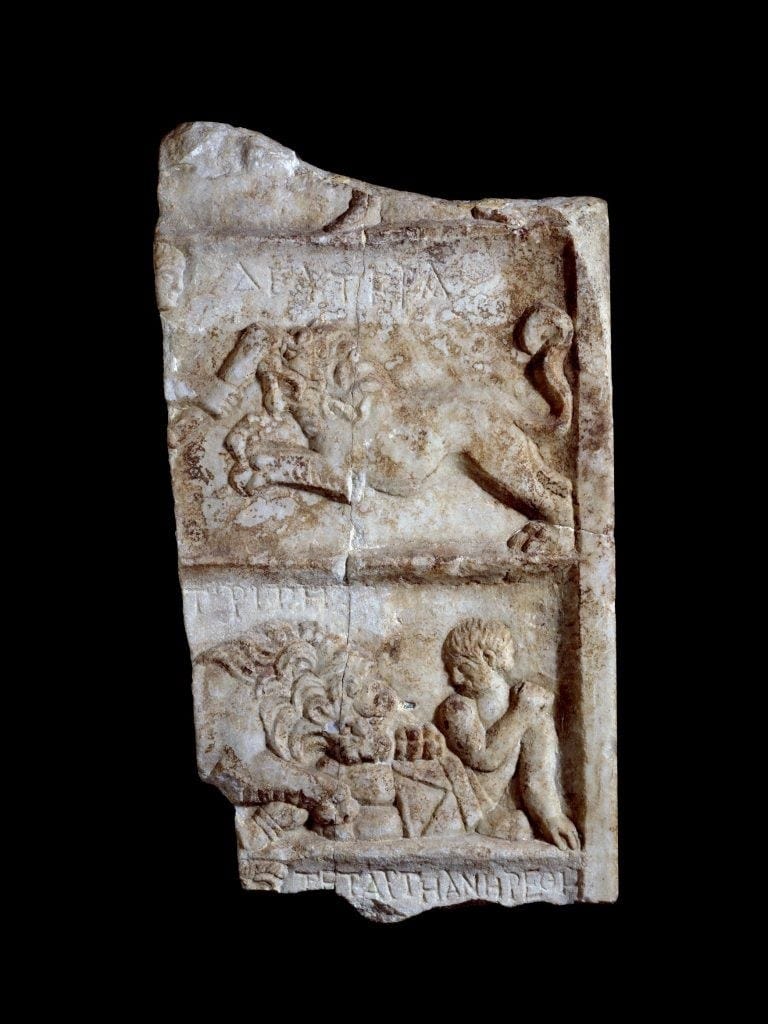

While images of gladiators being bitten by lions have appeared in ancient mosaics and pottery, the discovery is the only convincing skeletal evidence using forensic experiments anywhere in the world of bite marks produced by the teeth of a large cat, such as a lion.

The findings centre on a single skeleton discovered in a Roman-period cemetery in York, a site believed to contain the remains of gladiators.

The individual’s bones exhibited distinct lesions that, upon close examination and comparison with modern zoological specimens, were identified as bite marks from a large feline species.

The bite marks on the pelvis of the skeleton represent the first confirmation of human interaction with large carnivores in a combat or entertainment setting in the Roman world.

Professor Becky Gowland, of the Department of Archaeology at Durham University, said: “This is an exciting new analysis and the first direct evidence of human-animal spectacle in Roman Britain and beyond. It also raises important questions about the importance and transport of exotic animals across the Roman Empire.”

The study contributes a vital new dimension to knowledge of Roman Britain, reinforcing the region’s deep connection to the empire’s entertainment traditions.

It highlights the brutality of these spectacles and their reach beyond Rome’s core territories.

The research was led by Tim Thompson, Professor of Anthropology at Maynooth University, Ireland.

He said: “For years, our understanding of Roman gladiatorial combat and animal spectacles has relied heavily on historical texts and artistic depictions.

“This discovery provides the first direct, physical evidence that such events took place in this period, reshaping our perception of Roman entertainment culture in the region.”