REVIEW: London Philharmonic Orchestra at The Glasshouse

Mahler’s ‘Fifth’ was on the menu as Wembley worries niggled

As a sizeable proportion of Tyneside was putting on a show of strength in the capital on Sunday, a significant cohort had travelled in the opposite direction to do likewise at The Glasshouse.

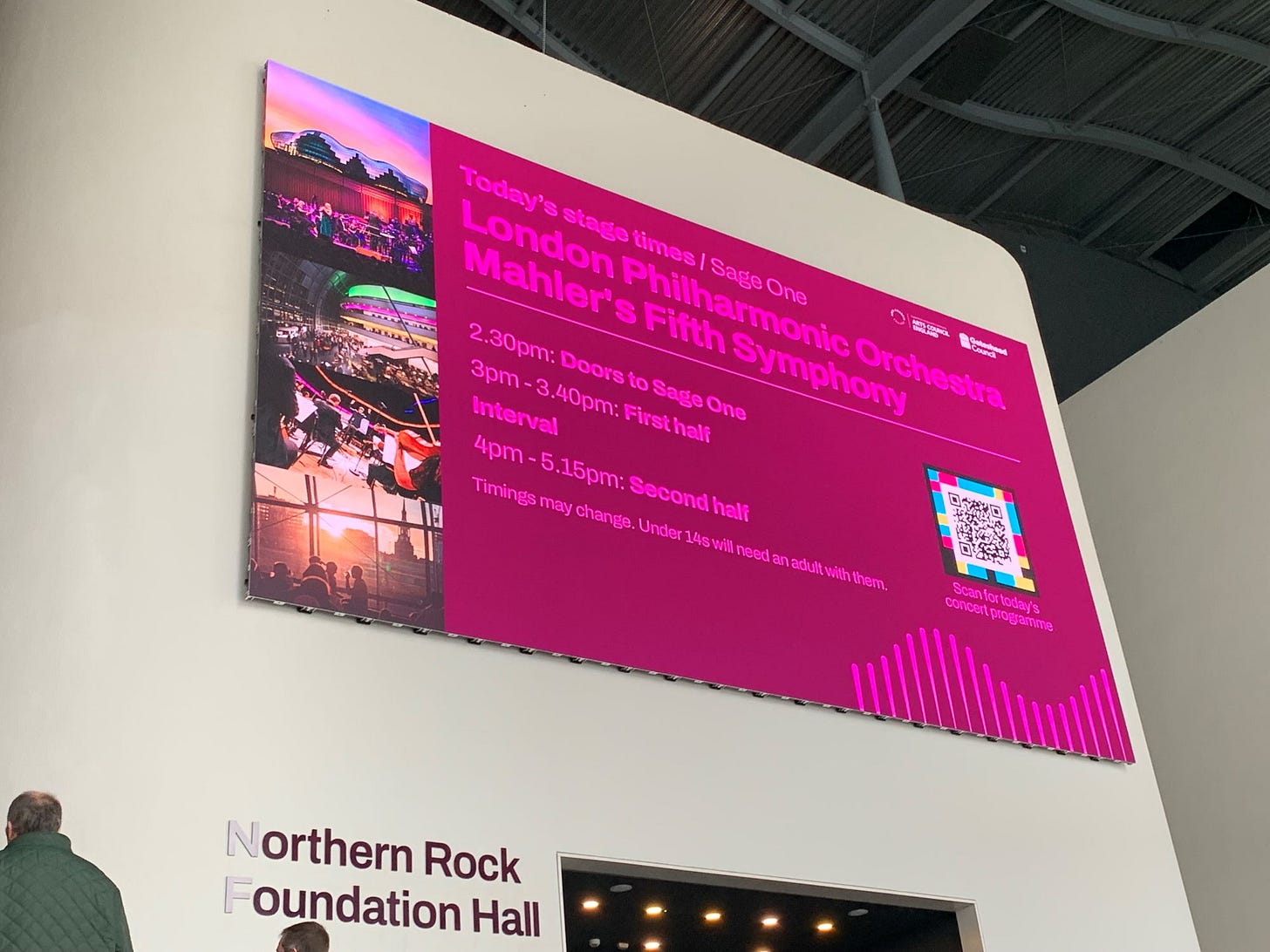

On the main stage of Gateshead’s international centre for music, the London Philharmonic was out in force for a fabulous concert during which a packed house seemed to hold its collective breath.

Mahler’s Fifth Symphony – not lightly undertaken and seldom heard in the North East, but calling for an orchestra’s big guns.

So there on the right were eight double basses and at the back and to the left the golden prow of a harp. Up above stood a man clashing mighty cymbals, as arresting to the eye as the ear, and a tuba player who had recourse only once to a mute the size of a traffic cone.

It was big, big stuff, and in between were top class musicians of every stripe, including principal flute Juliette Bausor surveying a scene that will have been familiar as a one-time leading light of Royal Northern Sinfonia.

But if the Mahler was the main course, there was a brilliant starter with Swiss virtuoso Francesco Piemontesi at the sleek black ‘grand’ for the Robert Schumann Piano Concerto.

Throughout he seemed engaged in a musical ‘conversation’ with the orchestra which far from excluding the audience invited us in. It was fine playing, unshowy but meticulous.

The applause, finally, was exuberant. Piemontesi, hailed by conductor Robin Ticciati, seemed genuinely moved and eventually returned to the stool for a solo encore - one of Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words, I was told. Others will have known it. Breathtakingly beautiful is all I can say.

After the interval, the Mahler - homage to a composer who didn’t see the need to do things by halves and socked it to us in his Fifth Symphony, premiered in Cologne in 1904.

Five movements over about 70 minutes and it begins with the sort of climax many compositions work their way up to – the trumpet’s clarion call (principal Paul Beniston, busy throughout) and the cymbals man describing his first flamboyant arc in the air.

My first time hearing this piece performed live and I would liken it to several movie scores all in one, not that Mahler would have known anything about that.

Umpteen mood changes, from sombre, almost funereal at times, to jaunty with a percussive hint of sleigh rides; from contemplative to full-on militaristic; the whole decidedly epic, an unfolding story with several subplots fighting for supremacy.

Ticciati, British but of Italian heritage, held it all together, summoning, coaxing and sometimes calming beneath his flopping curls. The five movements flew, the music relentless and the sudden punctuating silences immaculate and dramatic (cue for throat-clearing coughs held in by an audience hanging on every note).

More thunderous applause at the end and a partial standing ovation – and, I have to report, from some sections of the audience, a rather hasty exit after decent time had elapsed.

Out on the concourse mobile phones were quickly on, the tinny sound of commentary following Mahler’s masterpiece.

For some, I feel sure, the pre-concert inner debate had run: ‘the match or Mahler? Mahler or the match?’

For those who opted for the concert, to which many must have already committed, the omens for Cup Final victory had been good. The orchestra was in black and white – well, white dress shirts and dickie bows under black jackets for the men.

From London (Wembley) the news was more than encouraging, which for those of a black-and-white footballing persuasion added lustre to a tremendous afternoon in this great concert hall.

Mahler, at least on this occasion, could be hailed as a ‘Mag’.