Review: Manhunt, Royal Court Theatre

Susan Wear reports back from Robert Icke's uncomfortable study on the life and death of Raoul Moat

Stockton-born Robert Icke, best known for his hugely successful adaptations of classic plays, tackles his first original drama in this production based on the true story of the life and death of Raoul Moat, the infamous fugitive who sparked Britain’s largest manhunt.

It’s a monster of a co-production with Sonia Friedman Productions starring Samuel Edward-Cook with Trevor Fox, Leo James, Patricia Jones, Danny Kirrane, Angela Lonsdale, Sally Messham and Nicholas Tennant.

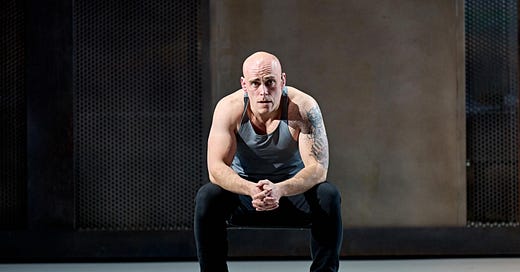

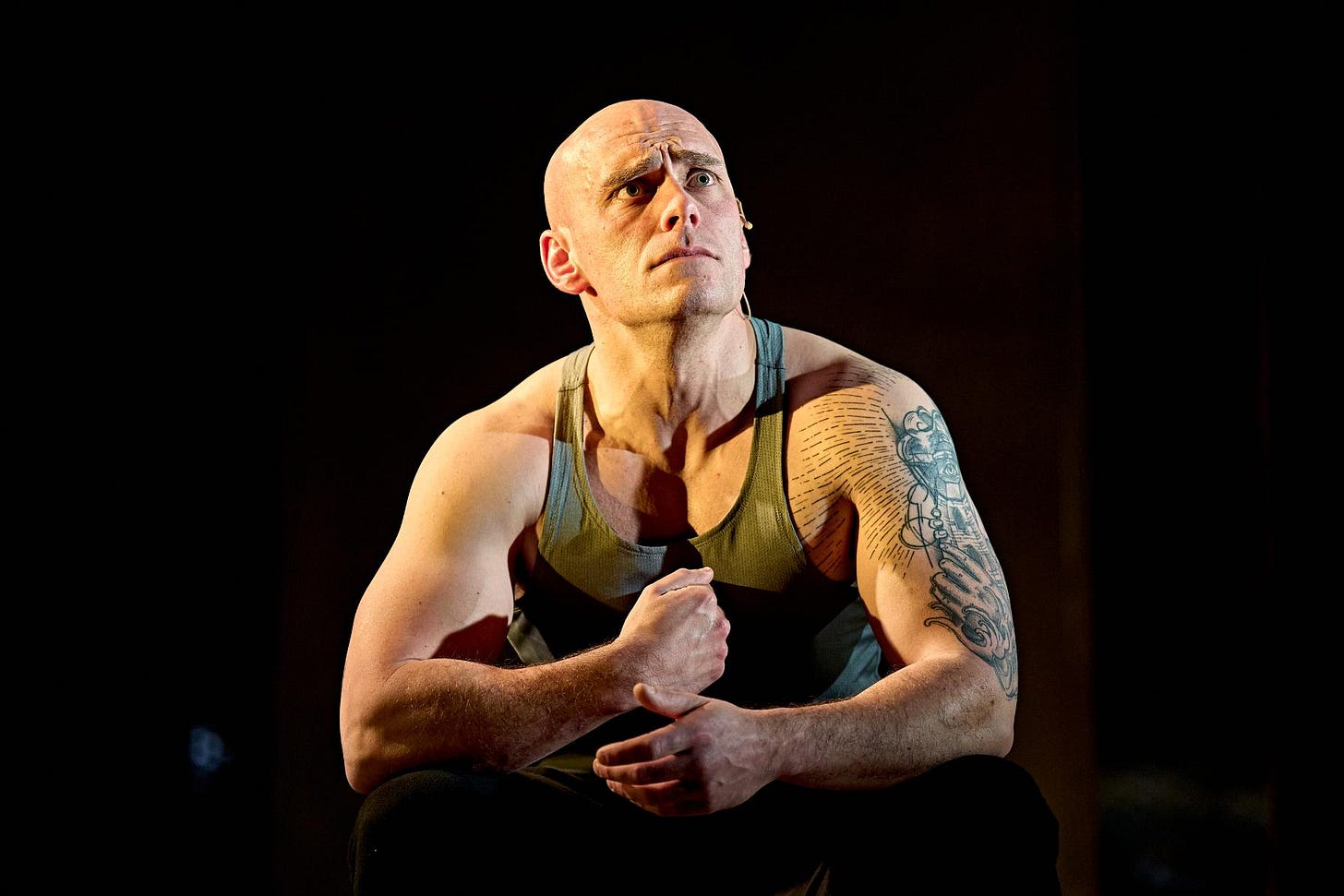

Moat’s version of his story, as far as it can be known, begins as the audience take their seats; his bulky track-suited figure paces his cell, doing push ups and banging on the walls. Above his head a camera films every move and simultaneously projects the scene onto the cell wall – a topsy turvy video installation that emphasises his palpable frustration, anger and terrifying confusion.

Two days later Moat has acquired a sawn-off shotgun and is outside his ex-partner’s home listening through an open window, and again the video technique, accompanied by loud party music serves to magnify his belief that she and her new boyfriend are laughing at him.

Out of fear, his ex-partner had told him that the new boyfriend was a policeman, further fuelling the former nightclub bouncer’s hatred of Northumbria Police, who he believed had long been persecuting him. He did not hesitate to brutally shoot the martial arts teacher on the doorstep, making sure after three shots he would be dead, and then fired once at Samantha, critically injuring her.

From then, he was on the run, albeit in communication with the police and aided and abetted by two co- conspirators (who are still serving lengthy jail sentences).

In his rage he threatens to kill every policeman he sees and PC David Rathband, sitting defenceless alone in his patrol car, is his next victim who is shot in the face through the car window.

The experience is recreated as a blinding white light fills the auditorium and then plunges into pitch darkness while the voice of PC Rathband describes not only his terror at being blinded but his desperate attempts to rehabilitate. At one point he posts on social media he lost his job, his wife, his sight. Later he took his own life just before he was due to run with the Olympic torch, which instead was carried by his daughter, wearing a blindfold.

But this play is about Raoul Moat. Much of it relates to what those of us who followed those shocking events in July 2010, will recognise, though it skirts the unedifying media circus, the rubbernecking, and the mystifying crusade of public support martyrising Moat on line.

It does include presumably imagined scenes – in one footballer Paul Gascoigne turns up to bring him food and gives him an empathising pep talk. Gazza famously did turn up, mistaking Moat for a friend with a similar name, but wasn’t allowed near. At this and at a couple of other points, Moat is obliged to tell the audience ‘that didn’t happen.’

Holed up in a tent in a field in Rothbury, Northumberland, Moat talks about his upbringing by his grandmother, after his mother is diagnosed with bipolar disorder and fantasises about the life he wants – in a rural idyll with Sam and his three children (variously played by Zoe Bryan, Nathan Jogo, Madeleine Mckenna and Odhran Ridell).

Moat believes he is a victim, as if he had no choices. His friends (pretending to be hostages) joke that one day actors might be playing them in a film. It may be the reason why there’s practically no mention of the other victims, their families or the impact this appalling crime had on them is to shock and re-assert the terrible toxic masculinity displayed by Moat, but it feels uncomfortable.

Samuel Edward-Cook does a very good job of a Raoul Moat who feels persecuted, telling everyone he’s the victim, until he and others believe it too. In his mind he did what he did because everyone else was stopping him from getting what he wanted.

Portraying such raging and hatred must take its toll on any actor, but Edward-Cook was menacing, terrifying and ultimately frighteningly believable.

It’s 15 years since Moat had apparently asked for psychiatric help before he left prison. Who knows if that might have made a difference, or if we could have spotted and tackled the dangerous machismo that is spiralling out of control in young men, inspired by Andrew Tate and others who think it’s ok to take what they want regardless of who gets in the way.

Manhunt is at the Royal Court, London until May 3. Tickets from the website.